Christmas In Ritual and Tradition, Christian and Pagan

by Clement A. Miles

Published by T. Fisher Unwin

1912

Project Gutenberg

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

The Origin and Purpose of Festivals—Ideas suggested by Christmas—Pagan and Christian Elements—The Names of the Festival—Foundation of the Feast of the Nativity—Its Relation to the Epiphany—December 25 and the Natalis Invicti—The Kalends of January—Yule and Teutonic Festivals—The Church and Pagan Survivals—Two Conflicting Types of Festival—Their Interaction—Plan of the Book.

Christmas, as we have seen, had its beginning at the middle of the fourth century in Rome. The new feast was not long in finding a hymn-writer to embody in immortal Latin the emotions called forth by the memory of the Nativity. “Veni, redemptor gentium” is one of the earliest of Latin hymns—one of the few that have come down to us from the father of Church song, Ambrose, Archbishop of Milan (d. 397). Great as theologian and statesman, Ambrose was great also as a poet and systematizer of Church music. “Veni, redemptor gentium” is above all things stately and severe, in harmony with the austere character of the zealous foe of the Arian heretics, the champion of monasticism. It is the theological aspect alone of Christmas, the redemption of sinful man by the mystery of the Incarnation and the miracle of the Virgin Birth, that we find in St. Ambrose's terse and pregnant Latin; there is no feeling for the human pathos and poetry of the scene at Bethlehem—

(Vienna: Imperial Gallery)

“Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her,

Ich bring euch gute neue Mär,

Der guten Mär bring ich so viel,

INTRODUCTION

The Origin and Purpose of Festivals—Ideas suggested by Christmas—Pagan and Christian Elements—The Names of the Festival—Foundation of the Feast of the Nativity—Its Relation to the Epiphany—December 25 and the Natalis Invicti—The Kalends of January—Yule and Teutonic Festivals—The Church and Pagan Survivals—Two Conflicting Types of Festival—Their Interaction—Plan of the Book.

It has been an instinct in nearly all peoples, savage or civilized, to set aside certain days for special ceremonial observances, attended by outward rejoicing. This tendency to concentrate on special times answers to man's need to lift himself above the commonplace and the everyday, to escape from the leaden weight of monotony that oppresses him. “We tend to tire of the most eternal splendours, and a mark on our calendar, or a crash of bells at midnight maybe, reminds us that we have only recently been created.” That they wake people up is the great justification of festivals, and both man's religious sense and his joy in life have generally tended to rise “into peaks and towers and turrets, into superhuman exceptions which really prove the rule.” It is difficult to be religious, impossible to be merry, at every moment of life, and festivals are as sunlit peaks, testifying, above dark valleys, to the eternal radiance. This is one view of the purpose and value of festivals, and their function of cheering people and giving them larger perspectives has no doubt been an important reason for their maintenance in the past. If we could trace the custom of festival-keeping back to its origins in primitive society we should find the same principle of specialization involved, though it is probable that the practice came into being not for the sake of its moral or emotional effect, but from man's desire to lay up, so to speak, a stock of sanctity, magical not ethical, for ordinary days.

The first holy-day-makers were probably more concerned with such material goods as food than with spiritual ideals, when they marked with sacred days the rhythm of the seasons. As man's consciousness developed, the subjective aspect of the matter would come increasingly into prominence, until in the festivals of the Christian Church the main object is to quicken the devotion of the believer by contemplation of the mysteries of the faith. Yet attached, as we shall see, to many Christian festivals, are old notions of magical sanctity, probably quite as potent in the minds of the common people as the more spiritual ideas suggested by the Church's feasts.

In modern England we have almost lost the festival habit, but if there is one feast that survives among us as a universal tradition it is Christmas. We have indeed our Bank Holidays, but they are mere days of rest and amusement, and for the mass of the people Easter and Whitsuntide have small religious significance—Christmas alone has the character of sanctity which marks the true festival. The celebration of Christmas has often little or nothing to do with orthodox dogma, yet somehow the sense of obligation to keep the feast is very strong, and there are few English people, however unconventional, who escape altogether the spell of tradition in this matter.

Christmas—how many images the word calls up: we think of carol-singers and holly-decked churches where people hymn in time-honoured strains the Birth of the Divine Child; of frost and snow, and, in contrast, of warm hearths and homes bright with light and colour, very fortresses against the cold; of feasting and revelry, of greetings and gifts exchanged; and lastly of vaguely superstitious customs, relics of long ago, performed perhaps out of respect for use and wont, or merely in jest, or with a deliberate attempt to throw ourselves back into the past, to re-enter for a moment the mental childhood of the race. These are a few of the pictures that rise pell-mell in the minds of English folk at the mention of Christmas; how many other scenes would come before us if we could realize what the festival means to men of other nations. Yet even these will suggest what hardly needs saying, that Christmas is something far more complex than a Church holy-day alone, that the celebration of the Birth of Jesus, deep and touching as is its appeal to those who hold the faith of the Incarnation, is but one of many elements that have entered into the great winter festival.

In the following pages I shall try to present a picture, sketchy and inadequate though it must be, of what Christmas is and has been to the peoples of Europe, and to show as far as possible the various elements that have gone into its make-up. Most people have a vague impression that these are largely pagan, but comparatively few have any idea of the process by which the heathen elements have become mingled with that which is obviously Christian, and equal obscurity prevails as to the nature and meaning of the non-Christian customs. The subject is vast, and has not been thoroughly explored as yet, but the labours of historians and folk-lorists have made certain conclusions probable, and have produced hypotheses of great interest and fascination.

I have spoken of “Christian” and “pagan” elements. The distinction is blurred to some extent by the clothing of heathen customs in a superficial Christianity, but on the whole it is clear enough to justify the division of this book into two parts, one dealing with the Church's feast of the Holy Birth, the other with those remains of pagan winter festivals which extend from November to January, but cluster especially round Christmas and the Twelve Days.

Before we pass to the various aspects of the Church's Christmas, we must briefly consider its origins and its relation to certain pagan festivals, the customs of which will be dealt with in detail in Part II.

Before we pass to the various aspects of the Church's Christmas, we must briefly consider its origins and its relation to certain pagan festivals, the customs of which will be dealt with in detail in Part II.

The names given to the feast by different European peoples throw a certain amount of light on its history. Let us take five of them—Christmas,Weihnacht, Noël, Calendas, and Yule—and see what they suggest.

I. The English Christmas and its Dutch equivalent Kerstmisse, plainly point to the ecclesiastical side of the festival; the German Weihnacht (sacred night) is vaguer, and might well be either pagan or Christian; in point of fact it seems to be Christian, since it does not appear till the year 1000, when the Faith was well established in Germany. Christmas and Weihnacht, then, may stand for the distinctively Christian festival, the history of which we may now briefly study.

When and where did the keeping of Christmas begin? Many details of its early history remain in uncertainty, but it is fairly clear that the earliest celebration of the Birth of Christ on December 25 took place at Rome about the middle of the fourth century, and that the observance of the day spread from the western to the eastern Church, which had before been wont to keep January 6 as a joint commemoration of the Nativity and the Baptism of the Redeemer.

The first mention of a Nativity feast on December 25 is found in a Roman document known as the Philocalian Calendar, dating from the year 354, but embodying an older document evidently belonging to the year 336. It is uncertain to which date the Nativity reference belongs; but further back than 336 at all events the festival cannot be traced.

From Rome, Christmas spread throughout the West, with the conversion of the barbarians. Whether it came to England through the Celtic Church is uncertain, but St. Augustine certainly brought it with him, and Christmas Day, 598, witnessed a great event, the baptism of more than ten thousand English converts. In 567 the Council of Tours had declared the Twelve Days, from Christmas to Epiphany, a festal tide; the laws of Ethelred (991-1016) ordained it to be a time of peace and concord among Christian men, when all strife must cease. In Germany Christmas was established by the Synod of Mainz in 813; in Norway by King Hakon the Good about the middle of the tenth century.

In the East, as has been seen, the Birth of the Redeemer was at first celebrated not on December 25, but on January 6, the feast of the Epiphany or manifestation of Christ's glory. The Epiphany can be traced as far back as the second century, among the Basilidian heretics, from whom it may have spread to the Catholic Church. It was with them certainly a feast of the Baptism, and possibly also of the Nativity, of Christ. The origins of the Epiphany festival are very obscure, nor can we say with certainty what was its meaning at first. It may be that it took the place of a heathen rite celebrating the birth of the World or Æon from the Virgin on January 6. At all events one of its objects was to commemorate the Baptism, the appearance of the Holy Dove, and the Voice from heaven, “Thou art my beloved son, in whom I am well pleased” (or, as other MSS. read, “This day have I begotten thee”).

In some circles of early Christianity the Baptism appears to have been looked upon as the true Birth of Christ, the moment when, filled by the Spirit, He became Son of God; and the carnal Birth was regarded as of comparatively little significance. Hence the Baptism festival may have arisen first, and the celebration of the Birth at Bethlehem may have been later attached to the same day, partly perhaps because a passage in St. Luke's Gospel was supposed to imply that Jesus was baptized on His thirtieth birthday. As however the orthodox belief became more sharply defined, increasing stress was laid on the Incarnation of God in Christ in the Virgin's womb, and it may have been felt that the celebration of the Birth and the Baptism on the same day encouraged heretical views. Hence very likely the introduction of Christmas on December 25 as a festival of the Birth alone. In the East the concelebration of the two events continued for some time after Rome had instituted the separate feast of Christmas. Gradually, however, the Roman use spread: at Constantinople it was introduced about 380 by the great theologian, Gregory Nazianzen; at Antioch it appeared in 388, at Alexandria in 432. The Church of Jerusalem long stood out, refusing to adopt the new feast till the seventh century, it would seem. One important Church, the Armenian, knows nothing of December 25, and still celebrates the Nativity with the Epiphany on January 6. Epiphany in the eastern Orthodox Church has lost its connection with the Nativity and is now chiefly a celebration of the Baptism of Christ, while in the West, as every one knows, it is primarily a celebration of the Adoration by the Magi, an event commemorated by the Greeks on Christmas Day. Epiphany is, however, as we shall see, a greater festival in the Greek Church than Christmas.

Such in bare outline is the story of the spread of Christmas as an independent festival. Its establishment fitly followed the triumph of the Catholic doctrine of the perfect Godhead or Christ at the Council of Nicea in 325.

II. The French Noël is a name concerning whose origin there has been considerable dispute; there can, however, be little doubt that it is the same word as the Provençal Nadau or Nadal, the Italian Natale, and the Welsh Nadolig, all obviously derived from the Latin natalis, and meaning “birthday.” One naturally takes this as referring to the Birth of Christ, but it may at any rate remind us of another birthday celebrated on the same date by the Romans of the Empire, that of the unconquered Sun, who on December 25, the winter solstice according to the Julian calendar, began to rise to new vigour after his autumnal decline.

Why, we may ask, did the Church choose December 25 for the celebration of her Founder's Birth? No one now imagines that the date is supported by a reliable tradition; it is only one of various guesses of early Christian writers. As a learned eighteenth-century Jesuit has pointed out, there is not a single month in the year to which the Nativity has not been assigned by some writer or other. The real reason for the choice of the day most probably was, that upon it fell the pagan festival just mentioned.

The Dies Natalis Invicti was probably first celebrated in Rome by order of the Emperor Aurelian (270-5), an ardent worshipper of the Syrian sun-god Baal. With the Sol Invictus was identified the figure of Mithra, that strange eastern god whose cult resembled in so many ways the worship of Jesus, and who was at one time a serious rival of the Christ in the minds of thoughtful men. It was the sun-god, poetically and philosophically conceived, whom the Emperor Julian made the centre of his ill-fated revival of paganism, and there is extant a fine prayer of his to “King Sun.”

What more natural than that the Church should choose this day to celebrate the rising of her Sun of Righteousness with healing in His wings, that she should strive thus to draw away to His worship some adorers of the god whose symbol and representative was the earthly sun! There is no direct evidence of deliberate substitution, but at all events ecclesiastical writers soon after the foundation of Christmas made good use of the idea that the birthday of the Saviour had replaced the birthday of the sun.

Little is known of the manner in which the Natalis Invicti was kept; it was not a folk-festival, and was probably observed by the classes rather than the masses. Its direct influence on Christmas customs has probably been little or nothing. It fell, however, just before a Roman festival that had immense popularity, is of great importance for our subject, and is recalled by another name for Christmas that must now be considered.

III. The Provençal Calendas or Calenos, the Polish Kolenda, the Russian Kolyáda, the Czech Koleda and the Lithuanian Kalledos, not to speak of the Welsh Calenig for Christmas-box, and the Gaelic Calluinn for New Year's Eve, are all derived from the Latin Kalendae, and suggest the connection of Christmas with the Roman New Year's Day, the Kalends or the first day of January, a time celebrated with many festive customs. What these were, and how they have affected Christmas we shall see in some detail in Part II.; suffice it to say here that the festival, which lasted for at least three days, was one of riotous life, of banqueting and games and licence. It was preceded, moreover, by theSaturnalia (December 17 to 23) which had many like features, and must have formed practically one festive season with it. The wordSaturnalia has become so familiar in modern usage as to suggest sufficiently the character of the festival for which it stands.

Into the midst of this season of revelry and licence the Church introduced her celebration of the beginning of man's redemption from the bondage of sin. Who can wonder that Christmas contains incongruous elements, for old things, loved by the people, cannot easily be uprooted.

IV. One more name yet remains to be considered, Yule (Danish Jul), the ordinary word for Christmas in the Scandinavian languages, and not extinct among ourselves. Its derivation has been widely discussed, but so far no satisfactory explanation of it has been found. Professor Skeat in the last edition of his Etymological Dictionary (1910) has to admit that its origin is unknown. Whatever its source may be, it is clearly the name of a Germanic season—probably a two-month tide covering the second half of November, the whole of December, and the first half of January. It may well suggest to us the element added to Christmas by the barbarian peoples who began to learn Christianity about the time when the festival was founded. Modern research has tended to disprove the idea that the old Germans held a Yule feast at the winter solstice, and it is probable, as we shall see, that the specifically Teutonic Christmas customs come from a New Year and beginning-of-winter festival kept about the middle of November. These customs transferred to Christmas are to a great extent religious or magical rites intended to secure prosperity during the coming year, and there is also the familiar Christmas feasting, apparently derived in part from the sacrificial banquets that marked the beginning of winter.

We have now taken a general glance at the elements which have combined in Christmas. The heathen folk-festivals absorbed by the Nativity feast were essentially life-affirming, they expressed the mind of men who said “yes” to this life, who valued earthly good things. On the other hand Christianity, at all events in its intensest form, the religion of the monks, was at bottom pessimistic as regards this earth, and valued it only as a place of discipline for the life to come; it was essentially a religion of renunciation that said “no” to the world. The Christian had here no continuing city, but sought one to come. How could the Church make a feast of the secular New Year; what mattered to her the world of time? her eye was fixed upon the eternal realities—the great drama of Redemption. Not upon the course of the temporal sun through the zodiac, but upon the mystical progress of the eternal Sun of Righteousness must she base her calendar. Christmas and New Year's Day—the two festivals stood originally for the most opposed of principles.

We have now taken a general glance at the elements which have combined in Christmas. The heathen folk-festivals absorbed by the Nativity feast were essentially life-affirming, they expressed the mind of men who said “yes” to this life, who valued earthly good things. On the other hand Christianity, at all events in its intensest form, the religion of the monks, was at bottom pessimistic as regards this earth, and valued it only as a place of discipline for the life to come; it was essentially a religion of renunciation that said “no” to the world. The Christian had here no continuing city, but sought one to come. How could the Church make a feast of the secular New Year; what mattered to her the world of time? her eye was fixed upon the eternal realities—the great drama of Redemption. Not upon the course of the temporal sun through the zodiac, but upon the mystical progress of the eternal Sun of Righteousness must she base her calendar. Christmas and New Year's Day—the two festivals stood originally for the most opposed of principles.

Naturally the Church fought bitterly against the observance of the Kalends; she condemned repeatedly the unseemly doings of Christians in joining in heathenish customs at that season; she tried to make the first of January a solemn fast; and from the ascetic point of view she was profoundly right, for the old festivals were bound up with a lusty attitude towards the world, a seeking for earthly joy and well-being.

The struggle between the ascetic principle of self-mortification, world-renunciation, absorption in a transcendent ideal, and the natural human striving towards earthly joy and well-being, is, perhaps, the most interesting aspect of the history of Christianity; it is certainly shown in an absorbingly interesting way in the development of the Christian feast of the Nativity. The conflict is keen at first; the Church authorities fight tooth and nail against these relics of heathenism, these devilish rites; but mankind's instinctive paganism is insuppressible, the practices continue as ritual, though losing much of their meaning, and the Church, weary of denouncing, comes to wink at them, while the pagan joy in earthly life begins to colour her own festival.

The Church's Christmas, as the Middle Ages pass on, becomes increasingly “merry”—warm and homely, suited to the instincts of ordinary humanity, filled with a joy that is of this earth, and not only a mystical rapture at a transcendental Redemption. The Incarnate God becomes a real child to be fondled and rocked, a child who is the loveliest of infants, whose birthday is the supreme type of all human birthdays, and may be kept with feasting and dance and song. Such is the Christmas of popular tradition, the Nativity as it is reflected in the carols, the cradle-rocking, the mystery plays of the later Middle Ages. This Christmas, which still lingers, though maimed, in some Catholic regions, is strongly life-affirming; the value and delight of earthly, material things is keenly felt; sometimes, even, it passes into coarseness and riot. Yet a certain mysticism usually penetrates it, with hints that this dear life, this fair world, are not all, for the soul has immortal longings in her. Nearly always there is the spirit of reverence, of bowing down before the Infant God, a visitor from the supernatural world, though bone of man's bone, flesh of his flesh. Heaven and earth have met together; the rough stable is become the palace of the Great King.

This we might well call the “Catholic” Christmas, the Christmas of the age when the Church most nearly answered to the needs of the whole man, spiritual and sensuous. The Reformation in England and Germany did not totally destroy it; in England the carol-singers kept up for a while the old spirit; in Lutheran Germany a highly coloured and surprisingly sensuous celebration of the Nativity lingered on into the eighteenth century. In the countries that remained Roman Catholic much of the old Christmas continued, though the spirit of the Counter-Reformation, faced by the challenge of Protestantism, made for greater “respectability,” and often robbed the Catholic Christmas of its humour, its homeliness, its truly popular stamp, substituting pretentiousness for simplicity, sugary sentiment for naïve and genuine poetry.

Apart from the transformation of the Church's Christmas from something austere and metaphysical into something joyous and human, warm and kindly, we shall note in our Second Part the survival of much that is purely pagan, continuing alongside of the celebration of the Nativity, and often little touched by its influence. But first we must consider the side of the festival suggested by the English and French names:Christmas will stand for the liturgical rites commemorating the wonder of the Incarnation—God in man made manifest—Noël or “the Birthday,” for the ways in which men have striven to realize the human aspect of the great Coming.

How can we reach the inner meaning of the Nativity feast, its significance for the faithful? Better, perhaps, by the way of poetry than by the way of ritual, for it is poetry that reveals the emotions at the back of the outward observances, and we shall understand these better when the singers of Christmas have laid bare to us their hearts. We may therefore first give attention to the Christmas poetry of sundry ages and peoples, and then go on to consider the liturgical and popular ritual in which the Church has striven to express her joy at the Redeemer's birth. Ceremonial, of course, has always mimetic tendencies, and in a further chapter we shall see how these issued in genuine drama; how, in the miracle plays, the Christmas story was represented by the forms and voices of living men.

Part I—The Christian Feast

CHAPTER II

CHRISTMAS POETRY

Ancient Latin Hymns, their Dogmatic, Theological Character—Humanizing Influence of Franciscanism—Jacopone da Todi's Vernacular Verse—German Catholic Poetry—Mediaeval English Carols.

MADONNA ENTHRONED WITH SAINTS AND ANGELS.

PESELLINO

(Empoli Gallery)

“Veni, redemptor gentium,

Ostende partum virginis;

Miretur omne saeculum:

Talis decet partus Deum.

Non ex virili semine,

Sed mystico spiramine,

Verbum Dei factum caro,

Fructusque ventris floruit.”

Ostende partum virginis;

Miretur omne saeculum:

Talis decet partus Deum.

Non ex virili semine,

Sed mystico spiramine,

Verbum Dei factum caro,

Fructusque ventris floruit.”

Another fine hymn often heard in English churches is of a slightly later date. “Corde natus ex Parentis” (“Of the Father's love begotten”) is a cento from a larger hymn by the Spanish poet Prudentius (c. 348-413). Prudentius did not write for liturgical purposes, and it was several centuries before “Corde natus” was adopted into the cycle of Latin hymns. Its elaborate rhetoric is very unlike the severity of “Veni, redemptor gentium,” but again the note is purely theological; the Incarnation as a world-event is its theme. It sings the Birth of Him who is

“Corde natus ex Parentis

Ante mundi exordium,

Alpha et O cognominatus,

Ipse fons et clausula

Omnium quae sunt, fuerunt,

Quaeque post futura sunt

Saeculorum saeculis.”

Ante mundi exordium,

Alpha et O cognominatus,

Ipse fons et clausula

Omnium quae sunt, fuerunt,

Quaeque post futura sunt

Saeculorum saeculis.”

Other early hymns are “A solis ortus cardine” (“From east to west, from shore to shore”), by a certain Coelius Sedulius (d. c. 450), still sung by the Roman Church at Lauds on Christmas Day, and “Jesu, redemptor omnium” (sixth century), the office hymn at Christmas Vespers. Like the poems of Ambrose and Prudentius, they are in classical metres, unrhymed, and based upon quantity, not accent, and they have the same general character, doctrinal rather than humanly tender.

In the ninth and tenth centuries arose a new form of hymnody, the Prose or Sequence sung after the Gradual (the anthem between the Epistle and Gospel at Mass). The earliest writer of sequences was Notker, a monk of the abbey of St. Gall, near the Lake of Constance. Among those that are probably his work is the Christmas “Natus ante saecula Dei filius.” The most famous Nativity sequence, however, is the “Laetabundus, exsultet fidelis chorus” of St. Bernard of Clairvaux (d. 1153), once sung all over Europe, and especially popular in England and France. Here are its opening verses:—

“Laetabundus,

Exsultet fidelis chorus;

Alleluia!

Regem regum

Intactae profudit thorus;

Res miranda!

Exsultet fidelis chorus;

Alleluia!

Regem regum

Intactae profudit thorus;

Res miranda!

Angelus consilii

Natus est de Virgine,

Sol de stella!

Sol occasum nesciens,

Stella semper rutilans,

Semper clara.”

Natus est de Virgine,

Sol de stella!

Sol occasum nesciens,

Stella semper rutilans,

Semper clara.”

The “Laetabundus” is in rhymed stanzas; in this it differs from most early proses. The writing of rhymed sequences, however, became common through the example of the Parisian monk, Adam of St. Victor, in the second half of the twelfth century. He adopted an entirely new style of versification and music, derived from popular songs; and he and his successors in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries wrote various proses for the Christmas festival.

If we consider the Latin Christmas hymns from the fourth century to the thirteenth, we shall find that however much they differ in form, they have one common characteristic: they are essentially theological—dwelling on the Incarnation and the Nativity as part of the process of man's redemption—rather than realistic. There is little attempt to imagine the scene in the stable at Bethlehem, little interest in the Child as a child, little sense of the human pathos of the Nativity. The explanation is, I think, very simple, and it lights up the whole observance of Christmas as a Church festival in the centuries we are considering: this poetry is the poetry of monks, or of men imbued with the monastic spirit.

The two centuries following the institution of Christmas saw the break-up of the Roman Empire in the west, and the incursions of barbarians threatening the very existence of the Christian civilization that had conquered classic paganism. It was by her army of monks that the Church tamed and Christianized the barbarians, and both religion and culture till the middle of the twelfth century were predominantly monastic. “In writing of any eminently religious man of this period” [the eleventh century], says Dean Church, “it must be taken almost as a matter of course that he was a monk.” And a monastery was not the place for human feeling about Christmas; the monk was—at any rate in ideal—cut off from the world; not for him were the joys of parenthood or tender feelings for a new-born child. To the monk the world was, at least in theory, the vale of misery; birth and generation were, one may almost say, tolerated as necessary evils among lay folk unable to rise to the heights of abstinence and renunciation; one can hardly imagine a true early Benedictine filled with “joy that a man is born into the world.” The Nativity was an infinitely important event, to be celebrated with a chastened, unearthly joy, but not, as it became for the later Middle Ages and the Renaissance, a matter upon which human affection might lavish itself, which imagination might deck with vivid concrete detail. In the later Christmas the pagan and the Christian spirit, or delight in earthly things and joy in the invisible, seem to meet and mingle; to the true monk of the Dark and Early Middle Ages they were incompatible.

What of the people, the great world outside the monasteries? Can we imagine that Christmas, on its Christian side, had a deep meaning for them? For the first ten centuries, to quote Dean Church again, Christianity “can hardly be said to have leavened society at all.... It acted upon it doubtless with enormous power; but it was as an extraneous and foreign agent, which destroys and shapes, but does not mingle or renew.... Society was a long time unlearning heathenism; it has not done so yet; but it had hardly begun, at any rate it was only just beginning, to imagine the possibility of such a thing in the eleventh century.”

“The practical religion of the illiterate,” says another ecclesiastical historian, Dr. W. R. W. Stephens, “was in many respects merely a survival of the old paganism thinly disguised. There was a prevalent belief in witchcraft, magic, sortilegy, spells, charms, talismans, which mixed itself up in strange ways with Christian ideas and Christian worship.... Fear, the note of superstition, rather than love, which is the characteristic of a rational faith, was conspicuous in much of the popular religion. The world was haunted by demons, hobgoblins, malignant spirits of divers kinds, whose baneful influence must be averted by charms or offerings.”

The writings of ecclesiastics, the decrees of councils and synods, from the fourth century to the eleventh, abound in condemnations of pagan practices at the turn of the year. It is in these customs, and in secular mirth and revelry, not in Christian poetry, that we must seek for the expression of early lay feeling about Christmas. It was a feast of material good things, a time for the fulfilment of traditional heathen usages, rather than a joyous celebration of the Saviour's birth. No doubt it was observed by due attendance at church, but the services in a tongue not understanded of the people cannot have been very full of meaning to them, and we can imagine their Christmas church-going as rather a duty inspired by fear than an expression of devout rejoicing. It is noteworthy that the earliest of vernacular Christmas carols known to us, the early thirteenth-century Anglo-Norman “Seignors, ore entendez à nus,” is a song not of religion but of revelry. Its last verse is typical:

“Seignors, jo vus di par Noël,

E par li sires de cest hostel,

Car bevez ben;

E jo primes beverai le men,

E pois aprèz chescon le soen,

Par mon conseil;

Si jo vus di trestoz, ‘Wesseyl!’

Dehaiz eit qui ne dirra, ‘Drincheyl!’”

E par li sires de cest hostel,

Car bevez ben;

E jo primes beverai le men,

E pois aprèz chescon le soen,

Par mon conseil;

Si jo vus di trestoz, ‘Wesseyl!’

Dehaiz eit qui ne dirra, ‘Drincheyl!’”

Not till the close of the thirteenth century do we meet with any vernacular Christmas poetry of importance. The verses of the troubadours and trouvères of twelfth-century France had little to do with Christianity; their songs were mostly of earthly and illicit love. The German Minnesingers of the thirteenth century were indeed pious, but their devout lays were addressed to the Virgin as Queen of Heaven, the ideal of womanhood, holding in glory the Divine Child in her arms, rather than to the Babe and His Mother in the great humility of Bethlehem.

The first real outburst of Christmas joy in a popular tongue is found in Italy, in the poems of that strange “minstrel of the Lord,” the Franciscan Jacopone da Todi (b. 1228, d. 1306). Franciscan, in that name we have an indication of the change in religious feeling that came over the western world, and especially Italy, in the thirteenth century. For the twenty all-too-short years of St. Francis's apostolate have passed, and a new attitude towards God and man and the world has become possible. Not that the change was due solely to St. Francis; he was rather the supreme embodiment of the ideals and tendencies of his day than their actual creator; but he was the spark that kindled a mighty flame. In him we reach so important a turning-point in the history of Christmas that we must linger awhile at his side.

Early Franciscanism meant above all the democratizing, the humanizing of Christianity; with it begins that “carol spirit” which is the most winning part of the Christian Christmas, the spirit which, while not forgetting the divine side of the Nativity, yet delights in its simple humanity, the spirit that links the Incarnation to the common life of the people, that brings human tenderness into religion. The faithful no longer contemplate merely a theological mystery, they are moved by affectionate devotion to the Babe of Bethlehem, realized as an actual living child, God indeed, yet feeling the cold of winter, the roughness of the manger bed.

St. Francis, it must be remembered, was not a man of high birth, but the son of a silk merchant, and his appeal was made chiefly to the traders and skilled workmen of the cities, who, in his day, were rising to importance, coming, in modern Socialist terms, to class-consciousness. The monks, although boys of low birth were sometimes admitted into the cloister, were in sympathy one with the upper classes, and monastic religion and culture were essentially aristocratic. The rise of the Franciscans meant the bringing home of Christianity to masses of town-workers, homely people, who needed a religion full of vivid humanity, and whom the pathetic story of the Nativity would peculiarly touch.

Love to man, the sense of human brotherhood—that was the great thing which St. Francis brought home to his age. The message, certainly, was not new, but he realized it with infectious intensity. The second great commandment, “Thou shall love thy neighbour as thyself,” had not indeed been forgotten by mediaeval Christianity; the common life of monasticism was an attempt to fulfil it; yet for the monk love to man was often rather a duty than a passion. But to St. Francis love was very life; he loved not by duty but by an inner compulsion, and his burning love of God and man found its centre in the God-man, Christ Jesus. For no saint, perhaps, has the earthly life of Christ been the object of such passionate devotion as for St. Francis; the Stigmata were the awful, yet, to his contemporaries, glorious fruit of his meditations on the Passion; and of the ecstasy with which he kept his Christmas at Greccio we shall read when we come to consider the Presepio. He had a peculiar affection for the festival of the Holy Child; “the Child Jesus,” says Thomas of Celano, “had been given over to forgetfulness in the hearts of many in whom, by the working of His grace, He was raised up again through His servant Francis.”

To the Early Middle Ages Christ was the awful Judge, the Rex tremendae majestatis, though also the divine bringer of salvation from sin and eternal punishment, and, to the mystic, the Bridegroom of the Soul. To Francis He was the little brother of all mankind as well. It was a new human joy that came into religion with him. His essentially artistic nature was the first to realize the full poetry of Christmas—the coming of infinity into extremest limitation, the Highest made the lowliest, the King of all kings a poor infant. He had, in a supreme degree, the mingled reverence and tenderness that inspire the best carols.

Though no Christmas verses by St. Francis have come down to us, there is a beautiful “psalm” for Christmas Day at Vespers, composed by him partly from passages of Scripture. A portion of Father Paschal Robinson's translation may be quoted:—

“Rejoice to God our helper.

Shout unto God, living and true,

With the voice of triumph.

For the Lord is high, terrible:

A great King over all the earth.

For the most holy Father of heaven,

Our King, before ages sent His Beloved

Son from on high, and He

was born of the Blessed Virgin,

holy Mary.

Shout unto God, living and true,

With the voice of triumph.

For the Lord is high, terrible:

A great King over all the earth.

For the most holy Father of heaven,

Our King, before ages sent His Beloved

Son from on high, and He

was born of the Blessed Virgin,

holy Mary.

* * * * *

This is the day which the Lord

hath made: let us rejoice and be glad in it.

For the beloved and most holy

Child has been given to us and

born for us by the wayside.

And laid in a manger because He

had no room in the inn.

Glory to God in the highest: and

on earth peace to men of good will.”

hath made: let us rejoice and be glad in it.

For the beloved and most holy

Child has been given to us and

born for us by the wayside.

And laid in a manger because He

had no room in the inn.

Glory to God in the highest: and

on earth peace to men of good will.”

It is in the poetry of Jacopone da Todi, born shortly after the death of St. Francis, that the Franciscan Christmas spirit finds its most intense expression. A wild, wandering ascetic, an impassioned poet, and a soaring mystic, Jacopone is one of the greatest of Christian singers, unpolished as his verses are. Noble by birth, he made himself utterly as the common people for whom he piped his rustic notes. “Dio fatto piccino” (“God made a little thing”) is the keynote of his music; the Christ Child is for him “our sweet little brother”; with tender affection he rejoices in endearing diminutives—“Bambolino,” “Piccolino,” “Jesulino.” He sings of the Nativity with extraordinary realism. Here, in words, is a picture of the Madonna and her Child that might well have inspired an early Tuscan artist:—

“Veggiamo il suo Bambino

Gammettare nel fieno,

E le braccia scoperte

Porgere ad ella in seno,

Ed essa lo ricopre

El meglio che può almeno,

Mettendoli la poppa

Entro la sua bocchina.

Gammettare nel fieno,

E le braccia scoperte

Porgere ad ella in seno,

Ed essa lo ricopre

El meglio che può almeno,

Mettendoli la poppa

Entro la sua bocchina.

* * * * *

A la sua man manca,

Cullava lo Bambino,

E con sante carole

Nenciava il suo amor fino....

Gli Angioletti d’ intorno

Se ne gian danzando,

Facendo dolci versi

E d’ amor favellando.”

Cullava lo Bambino,

E con sante carole

Nenciava il suo amor fino....

Gli Angioletti d’ intorno

Se ne gian danzando,

Facendo dolci versi

E d’ amor favellando.”

But there is an intense sense of the divine, as well as the human, in the Holy Babe; no one has felt more vividly the paradox of the Incarnation:—

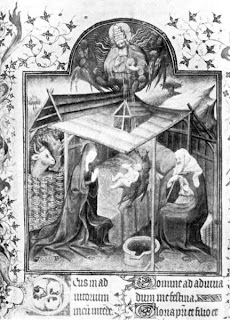

JACOPONE IN ECSTASY BEFORE THE VIRGIN.

From “Laude di Frate Jacopone da Todi”

(Florence, 1490).

“Ne la degna stalla del dolce Bambino

Gli Angeli cantano d’ intorno al piccolino;

Cantano e gridano gli Angeli diletti,

Tutti riverenti timidi e subietti,41

Al Bambolino principe de gli eletti,

Che nudo giace nel pungente spino.

* * * * *

Il Verbo divino, che è sommo sapiente,

In questo dì par che non sappia niente,

Guardal su’ l fieno, che gambetta piangente,

Como elli non fusse huomo divino.”[15]{13}

Here, again, are some sweet and homely lines about preparation for the Infant Saviour:—

“Andiamo a lavare

La casa a nettare,

Che non trovi bruttura.

Poi el menaremo,

Et gli daremo

Ben da ber’ e mangiare.

Un cibo espiato,

Et d’ or li sia dato

Senza alcuna dimura.

Lo cor adempito

Dagiamoli fornito

Senza odio ne rancura.”

There have been few more rapturous poets than Jacopone; men deemed him mad; but, “if he is mad,” says a modern Italian writer, “he is mad as the lark”—“Nessun poeta canta a tutta gola come questo frate minore. S’ è pazzo, è pazzo come l’ allodola.”

To him is attributed that most poignant of Latin hymns, the “Stabat Mater dolorosa”; he wrote also a joyous Christmas pendant to it:—

“Stabat Mater speciosa,

Juxta foenum gaudiosa,

Dum jacebat parvulus.

Cujus animam gaudentem,

Laetabundam ac ferventem,

Pertransivit jubilus.”

In the fourteenth century we find a blossoming forth of Christmas poetry in another land, Germany. There are indeed Christmas and Epiphany passages in a poetical Life of Christ by Otfrid of Weissenburg in the ninth century, and a twelfth-century poem by Spervogel, “Er ist gewaltic unde starc,” opens with a mention of Christmas, but these are of little importance for us. The fourteenth century shows the first real outburst, and that is traceable, in part at least, to the mystical movement in the Rhineland caused by the preaching of the great Dominican, Eckhart of Strasburg, and his followers. It was a movement towards inward piety as distinguished from, though not excluding, external observances, which made its way largely by sermons listened to by great congregations in the towns. Its impulse came not from the monasteries proper, but from the convents of Dominican friars, and it was for Germany in the fourteenth century something like what Franciscanism had been for Italy in the thirteenth. One of the central doctrines of the school 43was that of the Divine Birth in the soul of the believer; according to Eckhart the soul comes into immediate union with God by “bringing forth the Son” within itself; the historic Christ is the symbol of the divine humanity to which the soul should rise: “when the soul bringeth forth the Son,” he says, “it is happier than Mary.” Several Christmas sermons by Eckhart have been preserved; one of them ends with the prayer, “To this Birth may that God, who to-day is new born as man, bring us, that we, poor children of earth, may be born in Him as God; to this may He bring us eternally! Amen.” With this profound doctrine of the Divine Birth, it was natural that the German mystics should enter deeply into the festival of Christmas, and one of the earliest of German Christmas carols, “Es komt ein schif geladen,” is the work of Eckhart's disciple, John Tauler (d. 1361). It is perhaps an adaptation of a secular song:—

“A ship comes sailing onwards

With a precious freight on board;

It bears the only Son of God,

It bears the Eternal Word.”

The doctrine of the mystics, “Die in order to live,” fills the last verses:—

“Whoe'er would hope in gladness

To kiss this Holy Child,

Must suffer many a pain and woe,

Patient like Him and mild;

Must die with Him to evil

And rise to righteousness,

That so with Christ he too may share

Eternal life and bliss.”

To the fourteenth century may perhaps belong an allegorical carol still sung in both Catholic and Protestant Germany:—

“Es ist ein Ros entsprungen

Aus einer Wurzel zart,

Als uns die Alten sungen,

Von Jesse kam die Art,

Und hat ein Blümlein bracht,

Mitten im kalten Winter,

Wohl zu der halben Nacht.

Das Röslein, das ich meine,

Davon Jesajas sagt,

Hat uns gebracht alleine

Marie, die reine Magd.

Aus Gottes ew'gem Rat

Hat sie ein Kind geboren

Wohl zu der halben Nacht.”

In a fourteenth-century Life of the mystic Heinrich Suso it is told how one day angels came to him to comfort him in his sufferings, how they took him by the hand and led him to dance, while one began a glad song of the child Jesus, “In dulci jubilo.” To the fourteenth century, then, dates back that most delightful of German carols, with its interwoven lines of Latin. I may quote the fine Scots translation in the “Godlie and Spirituall Sangis” of 1567:—

“In dulci Jubilo, Now lat us sing with myrth and jo

Our hartis consolatioun lyis in praesepio,

And schynis as the Sone, Matris in gremio,

Alpha es et O, Alpha es et O.

O Jesu parvule! I thrist sore efter thé,

Confort my hart and mynde, O puer optime,

God of all grace sa kynde, et princeps gloriae

Trahe me post te, Trahe me post te.

Ubi sunt gaudia, in ony place bot thair,

Quhair that the Angellis sing Nova cantica,

Bot and the bellis ring in regis curia,

God gif I war thair, God gif I war thair.”

The music of “In dulci jubilo” has, with all its religious feeling, something of the nature of a dance, and unites in a strange fashion solemnity, playfulness, and ecstatic delight. No other air, perhaps, shows so perfectly the reverent gaiety of the carol spirit.

The fifteenth century produced a realistic type of German carol. Here is the beginning of one such:—

“Da Jesu Krist geboren wart,

do was es kalt;

in ain klaines kripplein

er geleget wart.

Da stunt ain esel und ain rint,

die atmizten über das hailig kint

gar unverborgen.

Der ain raines herze hat, der darf nit sorgen.”

It goes on to tell in naïve language the story of the wanderings of the Holy Family during the Flight into Egypt.

This carol type lasted, and continued to develop, in Austria and the Catholic parts of Germany through the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, and even in the nineteenth. In Carinthia in the early nineteenth century, almost every parish had its local poet, who added new songs to the old treasury. Particularly popular were the Hirtenlieder or shepherd songs, in which the peasant worshippers joined themselves to the shepherds of Bethlehem, and sought to share their devout 46emotions. Often these carols are of the most rustic character and in the broadest dialect. They breathe forth a great kindliness and homeliness, and one could fill pages with quotations. Two more short extracts must, however, suffice to show their quality.

How warm and hearty is their feeling for the Child:—

“Du herzliabste Muater, gib Acht auf dös Kind,

Es is ja gar frostig, thuas einfatschen gschwind.

Und du alter Voda, decks Kindlein schen zua,

Sonst hats von der Kölden und Winden kan Ruah.

Hiazt nemen mir Urlaub, o gettliches Kind,

Thua unser gedenken, verzeich unser Sünd.

Es freut uns von Herzen dass d'ankomen bist;

Es hätt uns ja niemand zu helfen gewist.”

And what fatherly affection is here:—

“Das Kind is in der Krippen glögn,

So herzig und so rar!

Mei klâner Hansl war nix dgögn,

Wenn a glei schener war.

Kolschwarz wie d'Kirchen d'Augen sein,

Sunst aber kreidenweiss;

Die Händ so hübsch recht zart und fein,

I hans angrürt mit Fleiss.

Aft hats auf mi an Schmutza gmacht,

An Höscheza darzue;

O warst du mein, hoan i gedacht,

Werst wol a munter Bue.

Dahoam in meiner Kachelstub

Liess i brav hoazen ein,

Do in den Stâl kimt überâl

Der kalte Wind herein.”

We have been following on German ground a mediaeval tradition that has continued unbroken down to modern days; but we must now take a leap backward in time, and consider the beginnings of the Christmas carol in England.

Not till the fifteenth century is there any outburst of Christmas poetry in English, though other forms of religious lyrics were produced in considerable numbers in the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. When the carols come at last, they appear in the least likely of all places, at the end of a versifying of the whole duty of man, by John Awdlay, a blind chaplain of Haghmon, in Shropshire. In red letters he writes:—

“I pray you, sirus, boothe moore and lase,

Sing these caroles in Cristëmas,”

and then follows a collection of twenty-five songs, some of which are genuine Christmas carols, as one now understands the word.

A carol, in the modern English sense, may perhaps be defined as a religious song, less formal and solemn than the ordinary Church hymn—an expression of popular and often naïve devotional feeling, a thing intended to be sung outside rather than within church walls. There still linger about the word some echoes of its original meaning, for “carol” had at first a secular or even pagan significance: in twelfth-century France it was used to describe the amorous song-dance which hailed the coming of spring; in Italian it meant a ring- or song-dance; while by English writers from the thirteenth to the sixteenth century it was used chiefly of singing joined with dancing, and had no necessary connection with religion. Much as the mediaeval Church, with its ascetic tendencies, disliked religious dancing, it could not always suppress it; and in Germany, as we shall see, there was choral dancing at Christmas round the cradle of the Christ Child. Whether Christmas carols were ever danced to in England is doubtful; many of the old airs and words have, however, a glee and playfulness as of human nature following its natural instincts of joy even in the celebration of the most sacred mysteries. It is probable that some of the carols are religious parodies of love-songs, written for the melodies of the originals, and many seem by their structure to be indirectly derived from the choral dances of farm folk, a notable feature being their burden or refrain, a survival of the common outcry of the dancers as they leaped around.

Awdlay's carols are perhaps meant to be sung by “wassailing neighbours, who make their rounds at Christmastide to drink a cup and take a gift, and bring good fortune upon the house”—predecessors of those carol-singers of rural England in the nineteenth century, whom Mr. Hardy depicts so delightfully in “Under the Greenwood Tree.” Carol-singing by a band of men who go from house to house is probably a Christianization of such heathen processions as we shall meet in less altered forms in Part II.

It must not be supposed that the carols Awdlay gives are his own work; and their exact date it is impossible to determine. Part of his book was composed in 1426, but one at least of the carols was probably written in the last half of the fourteenth century. They seem indeed to be the later blossomings of the great springtime of English literature, the period which produced Chaucer and Langland, an innumerable company of minstrels and ballad-makers, and the mystical poet, Richard Rolle of Hampole.

Through the fifteenth century and the first half of the sixteenth, the flowering continued; and something like two hundred carols of this period are known. It is impossible to attempt here anything like representative quotation; I can only sketch in roughest outline the main characteristics of English carol literature, and refer the reader for examples to Miss Edith Rickert's comprehensive collection, “Ancient English Carols, MCCCC-MDCC,” or to the smaller but fine selection in Messrs. E. K. Chambers and F. Sidgwick's “Early English Lyrics.” Many may have been the work of goliards or wandering scholars, and a common feature is the interweaving of Latin with English words.

Some, like the exquisite “I sing of a maiden that is makeles,” are rather songs to or about the Virgin than strictly Christmas carols; the Annunciation rather than the Nativity is their theme. Others again tell the whole story of Christ's life. The feudal idea is strong in such lines as these:—

“Mary is quene of allë thinge,

And her sone a lovely kinge.

God graunt us allë good endinge!

Regnat dei gracia.”

On the whole, in spite of some mystical exceptions, the mediaeval English carol is somewhat external in its religion; there is little deep individual feeling; the caroller sings as a member of the human race, whose curse is done away, whose nature is exalted by the Incarnation, rather than as one whose soul is athirst for God:—

“Now man is brighter than the sonne;

Now man in heven an hie shall wonne;

Blessëd be God this game is begonne

And his moder emperesse of helle.”

Salvation is rather an objective external thing than an inward and spiritual process. A man has but to pray devoutly to the dear Mother and Child, and they will bring him to the heavenly court. It is not so much personal sin as an evil influence in humanity, that is cured by the great event of Christmas:—

“It was dark, it was dim,

For men that levëd in gret sin;

Lucifer was all within,

Till on the Cristmes day.

There was weping, there was wo,

For every man to hell gan go.

It was litel mery tho,

Till on the Cristmes day.”

But now that Christ is born, and man redeemed, one may be blithe indeed:—

“Jhesus is that childës name,

Maide and moder is his dame,

And so oure sorow is turned to game.

Gloria tibi domine.

* * * * *

Now sitte we downe upon our knee,

And pray that child that is so free;

And with gode hertë now sing we

Gloria tibi domine.”

Sometimes the religious spirit almost vanishes, and the carol becomes little more than a gay pastoral song:—

“The shepard upon a hill he satt;

He had on him his tabard and his hat,

His tar-box, his pipe, and his flagat;

His name was called Joly Joly Wat,

For he was a gud herdës boy.

Ut hoy!

For in his pipe he made so much joy.

* * * * *

Whan Wat to Bedlem cum was,

He swet, he had gone faster than a pace;

He found Jesu in a simpell place,

Betwen an ox and an asse.

Ut hoy!

For in his pipe he made so much joy.

‘Jesu, I offer to thee here my pipe,

My skirt, my tar-box, and my scripe;

Home to my felowes now will I skipe,

And also look unto my shepe.’

Ut hoy!

For in his pipe he made so much joy.”

But to others again, especially the lullabies, the hardness of the Nativity, the shadow of the coming Passion, give a deep note of sorrow and pathos; there is the thought of the sword that shall pierce Mary's bosom:—

“This endris night I saw a sight,

A maid a cradell kepe,

And ever she song and seid among

‘Lullay, my child, and slepe.’

‘I may not slepe, but I may wepe,

I am so wo begone;

Slepe I wold, but I am colde

And clothës have I none.

* * * * *

‘Adam's gilt this man had spilt;

That sin greveth me sore.

Man, for thee here shall I be

Thirty winter and more.

* * * * *

‘Here shall I be hanged on a tree,

And die as it is skill.

That I have bought lesse will I nought;

It is my fader's will.’”

The lullabies are quite the most delightful, as they are the most human, of the carols. Here is an exquisitely musical verse from one of 1530:—

“In a dream late as I lay,

Methought I heard a maiden say

And speak these words so mild:

‘My little son, with thee I play,

And come,’ she sang, ‘by, lullaby.’

Thus rockëd she her child.

By-by, lullaby, by-by, lullaby,

Rockëd I my child.

By-by, by-by, by-by, lullaby,

Rockëd I my child. ”

CHAPTER III

CHRISTMAS POETRY (II)

The French Noël—Latin Hymnody in Eighteenth-century France—Spanish Christmas Verse—Traditional Carols of Many Countries—Christmas Poetry in Protestant Germany—Post-Reformation Verse in England—Modern English Carols.

THE ADORATION OF THE SHEPHERDS.

By Fouquet.

(Musée Condé, Chantilly.)

The Reformation marks a change in the character of Christmas poetry in England and the larger part of Germany, and, instead of following its development under Protestantism, it will be well to break off and turn awhile to countries where Catholic tradition remained unbroken. We shall come back later to Post-Reformation England and Protestant Germany.

In French there is little or no Christmas poetry, religious in character, before the fifteenth century; the earlier carols that have come down to us are songs rather of feasting and worldly rejoicing than of sacred things. The true Noël begins to appear in fifteenth-century manuscripts, but it was not till the following century that it attained its fullest vogue and was spread all over the country by the printing presses. Such Noëls seem to have been written by clerks or recognized poets, either for old airs or for specially composed music. “To a great extent,” says Mr. Gregory Smith, “they anticipate the spirit which stimulated the Reformers to turn the popular and often obscene songs into good and godly ballads.”

Some of the early Noëls are not unlike the English carols of the period, and are often half in Latin, half in French. Here are a few such “macaronic” verses:—

“Célébrons la naissance

Nostri Salvatoris,

Qui fait la complaisance

Dei sui Patris.

Cet enfant tout aimable,

In nocte mediâ,

Est né dans une étable,

De castâ Mariâ.

* * * * *

Mille esprits angéliques,

Juncti pastoribus,

Chantent dans leur musique,

Puer vobis natus,

Au Dieu par qui nous sommes,

Gloria in excelsis,

Et la paix soit aux hommes

Bonae voluntatis.

* * * * *

Qu'on ne soit insensible!

Adeamus omnes

A Dieu rendu passible,

Propter nos mortales,

Et tous, de compagnie,

Deprecemur eum

Qu’à la fin de la vie,

Det regnum beatum.”

The sixteenth century is the most interesting Noël period; we find then a conflict of tendencies, a conflict between Gallic realism and broad humour and the love of refined language due to the study of the ancient classics. There are many anonymous pieces of this time, but three important Noëlistes stand out by name: Lucas le Moigne, Curé of Saint Georges, Puy-la-Garde, near Poitiers; Jean Daniel, called “Maître Mitou,” a priest-organist at Nantes; and Nicholas Denisot of Le Mans, whose Noëls appeared posthumously under the pseudonym of “Comte d'Alsinoys.”

Lucas le Moigne represents the esprit gaulois, the spirit that is often called “Rabelaisian,” though it is only one side of the genius of Rabelais. The good Curé was a contemporary of the author of “Pantagruel.” His “Chansons de Noëls nouvaulx” was published in 1520, and contains carols in very varied styles, some naïve and pious, others hardly quotable at the present day. One of his best-known pieces is a dialogue between the Virgin and the singers of the carol: Mary is asked and answers questions about the wondrous happenings of her life. Here are four verses about the Nativity:—

“Or nous dites, Marie,

Les neuf mois accomplis,

Naquit le fruit de vie,

Comme l'Ange avoit dit?

—Oui, sans nulle peine

Et sans oppression,

Naquit de tout le monde

La vraie Rédemption.

Or nous dites, Marie,

Du lieu impérial,

Fut-ce en chambre parée,

Ou en Palais royal?

—En une pauvre étable

Ouverte à l'environ

Ou n'avait feu, ni flambe

Ni latte, ni chevron.

Or nous dites, Marie,

Qui vous vint visiter;

Les bourgeois de la ville

Vous ont-ils confortée?

—Oncque, homme ni femme

N'en eut compassion,

Non plus que d'un esclave

D’étrange région.

* * * * *

Or nous dites, Marie,

Des pauvres pastoureaux

Qui gardaient ès montagnes

Leurs brebis & aigneaux.

—Ceux-là m'ont visitée

Par grande affection;

Moult me fut agréable

Leur visitation.”

The influence of the “Pléiade,” with its care for form, its respect for classical models, its enrichment of the French tongue with new Latin words, is shown by Jean Daniel, who also owes something to the poets of the late fifteenth century. Two stanzas may be quoted from him:—

“C'est ung très grant mystère

Qu'ung roy de si hault pris

Vient naistre en lieu austère,

En si meschant pourpris:

Le Roy de tous les bons espritz,

C'est Jésus nostre frère,

Le Roy de tous les bons espritz,

Duquel sommes apris.

Saluons le doulx Jésuchrist,

Notre Dieu, notre frère,

Saluons le doulx Jésuchrist,

Chantons Noel d'esprit!

* * * * *

En luy faisant prière,

Soyons de son party,

Qu'en sa haulte emperière

Ayons lieu de party;

Comme il nous a droict apparty,

Jésus nostre bon frère,

Comme il nous a droict apparty

Au céleste convy.

Saluons, etc.

Amen. Noel.”

As for Denisot, I may give two charming verses from one of his pastorals:—

“Suz, Bergiez, en campaigne,

Laissez là vos troppeaux,

Avant qu'on s'accompaigne,

Enflez vos chalumeaux.

* * * * *

Enflez vos cornemuses,

Dansez ensemblement,

Et vos doucettes muses,

Accollez doucement.”

One result of the Italian influences which came over France in the sixteenth century was a fondness for diminutives. Introduced into carols, these have sometimes a very graceful effect:—

“Entre le boeuf & le bouvet,

Noel nouvellet,

Voulust Jésus nostre maistre,

En un petit hostelet,

Noel nouvellet,

En ce pauvre monde naistre,

O Noel nouvellet!

Ne couche, ne bercelet,

Noel nouvellet,

Ne trouvèrent en cette estre,

Fors ung petit drappelet,

Noel nouvellet,

Pour envelopper le maistre,

O Noel nouvellet!”

These diminutives are found again, though fewer, in a particularly delightful carol:—

“Laissez paître vos bestes

Pastoureaux, par monts et par vaux;

Laissez paître vos bestes,

Et allons chanter Nau.

J'ai ouï chanter le rossignol,

Qui chantoit un chant si nouveau,

Si haut, si beau,

Si résonneau,

Il m'y rompoit la tête,

Tant il chantoit et flageoloit:

Adonc pris ma houlette

Pour aller voir Naulet.

Laissez paître, etc.”

The singer goes on to tell how he went with his fellow-shepherds and shepherdesses to Bethlehem:—

“Nous dîmes tous une chanson

Les autres en vinrent au son,

Chacun prenant

Son compagnon:

Je prendrai Guillemette,

Margot tu prendras gros Guillot;

Qui prendra Péronelle?

Ce sera Talebot.

Laissez paître, etc.

Ne chantons plus, nous tardons trop,

Pensons d'aller courir le trot.

Viens-tu, Margot?—

J'attends Guillot.—

J'ai rompu ma courette,

Il faut ramancher mon sabot.—

Or, tiens cette aiguillette,

Elle y servira trop.

Laissez paître, etc.

* * * * *

Nous courumes de grand’ roideur

Pour voir notre doux Rédempteur

Et Créateur

Et Formateur,

Qui était tendre d'aage

Et sans linceux en grand besoin,

Il gisait en la crêche

Sur un botteau de foin.

Laissez paître, etc.

Sa mère avecque lui était:

Et Joseph si lui éclairait,

Point ne semblait

Au beau fillet,

Il n’était point son père;

Je l'aperçus bien au cameau (visage)

Il semblait à sa mère,

Encore est-il plus beau.

Laissez paître, etc.”

This is but one of a large class of French Noëls which make the Nativity more real, more present, by representing the singer as one of a company of worshippers going to adore the Child. Often these are shepherds, but sometimes they are simply the inhabitants of a parish, a town, a countryside, or a province, bearing presents of their own produce to the little Jesus and His parents. Barrels of wine, fish, fowls, sucking-pigs, pastry, milk, fruit, firewood, birds in a cage—such are their homely gifts. Often there is a strongly satiric note: the peculiarities and weaknesses of individuals are hit off; the reputation of a place is suggested, a village whose people are famous for their stinginess offers cider that is half rain-water; elsewhere the inhabitants are so given to law-suits that they can hardly find time to go to Bethlehem.

Such Noëls with their vivid local colour, are valuable pictures of the manners of their time. They are, unfortunately, too long for quotation here, but any reader who cares to follow up the subject will find some interesting specimens in a little collection of French carols that can be bought for ten centimes. They are of various dates; some probably were written as late as the eighteenth century. In that century, and indeed in the seventeenth, the best Christmas verses are those of a provincial and rustic character, and especially those in patois; the more cultivated poets, with their formal classicism, can ill enter into the spirit of the festival. Of the learned writers the best is a woman, Françoise Paschal, of Lyons (b. about 1610); in spite of her Latinity she shows a real feeling for her subjects. Some of her Noëls are dialogues between the sacred personages; one presents Joseph and Mary as weary wayfarers seeking shelter at all the inns of Bethlehem and everywhere refused by host or hostess:—

“Saint Joseph.

Voyons la Rose-Rouge.

Madame de céans,

Auriez-vous quelque bouge

Pour de petites gens?

L'Hôtesse.

Vous n'avez pas la mine

D'avoir de grands trésors;

Voyez chez ma voisine,

Car, quant à moi, je dors.

Saint Joseph.

Monsieur des Trois-Couronnes,

Avez-vous logement,

Chez vous pour trois personnes,

Quelque trou seulement.

L'Hôte.

Vous perdez votre peine,

Vous venez un peu tard,

Ma maison est fort pleine,

Allez quelqu'autre part.”

The most remarkable of the patois Noëlistes of the seventeenth century are the Provençal Saboly and the Burgundian La Monnoye, the one kindly and tender, the other witty and sarcastic. Here is one of Saboly's Provençal Noëls:—

“Quand la mièjonue sounavo,

Ai sautà dóu liech au sòu;

Ai vist un bèl ange que cantavo

Milo fes pu dous qu'un roussignòu.

Lei mastin dóu vesinage

Se soun toutes atroupa;

N'avien jamai vist aquéu visage

Se soun tout-d'un-cop mes à japa.

Lei pastre dessus la paio

Dourmien coume de soucas;

Quand an aussi lou bru dei sounaio

Au cresegu qu'ero lou souiras.

S'eron de gent resounable,

Vendrien sèns èstre envita:

Trouvarien dins un petit estable

La lumiero emai la verita.”

As for La Monnoye, here is a translation of one of his satirical verses:—“When in the time of frost Jesus Christ came into the world the ass and ox warmed Him with their breath in the stable. How many asses and oxen I know in this kingdom of Gaul! How many asses and oxen I know who would not have done as much!”

Apart from the rustic Noëls, the eighteenth century produced little French Christmas poetry of any charm. Some of the carols most sung in French churches to-day belong, however, to this period, e.g., the “Venez, divin Messie” of the Abbé Pellegrin.

One cannot leave the France of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries without some mention of its Latin hymnody. From a date near 1700, apparently, comes the sweet and solemn “Adeste, fideles”; by its music and its rhythm, perhaps, rather than by its actual words it has become the best beloved of Christmas hymns. The present writer has heard it sung with equal reverence and heartiness in English, German, French, and Italian churches, and no other hymn seems so full of the spirit of Christmas devotion—wonder, awe, and tenderness, and the sense of reconciliation between Heaven and earth. Composed probably in France, “Adeste, fideles” came to be used in English as well as French Roman Catholic churches during the eighteenth century. In 1797 it was sung at the chapel of the Portuguese Embassy in London; hence no doubt its once common name of “Portuguese hymn.” It was first used in an Anglican church in 1841, when the Tractarian Oakley translated it for his congregation at Margaret Street Chapel, London.

Another fine Latin hymn of the eighteenth-century French Church is Charles Coffin's “Jam desinant suspiria.” It appeared in the Parisian Breviary in 1736, and is well known in English as “God from on high hath heard.”

The Revolution and the decay of Catholicism in France seem to have killed the production of popular carols. The later nineteenth century, however, saw a revival of interest in the Noël as a literary form. In 1875 the bicentenary of Saboly's death was celebrated by a competition for a Noël in the Provençal tongue, and something of the same kind has been done in Brittany. The Noël has attracted by its aesthetic charm even poets who are anything but devout; Théophile Gautier, for instance, wrote a graceful Christmas carol, “Le ciel est noir, la terre est blanche.”

On a general view of the vernacular Christmas poetry of France it must be admitted that the devotional note is not very strong; there is indeed a formal reverence, a courtly homage, paid to the Infant Saviour, and the miraculous in the Gospel story is taken for granted; but there is little sense of awe and mystery. In harmony with the realistic instincts of the nation, everything is dramatically, very humanly conceived; at times, indeed, the personages of the Nativity scenes quite lose their sacred character, and the treatment degenerates into grossness. At its best, however, the French Noël has a gaiety and a grace, joined to a genuine, if not very deep, piety, that are extremely charming. Reading these rustic songs, we are carried in imagination to French countrysides; we think of the long walk through the snow to the Midnight Mass, the cheerful réveillon spread on the return, the family gathered round the hearth, feasting on wine and chestnuts and boudins, and singing in traditional strains the joys of Noël.

Across the Pyrenees, in Spain, the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries saw a great output of Christmas verse. Among the chief writers were Juan López de Ubeda, Francisco de Ocaña, and José de Valdivielso. Their villancicos remind one of the paintings of Murillo; they have the same facility, the same tender and graceful sentiment, without much depth. They lack the homely flavour, the quaintness that make the French and German folk-carols so delightful; they have not the rustic tang, and yet they charm by their simplicity and sweetness.

Here are a few stanzas by Ocaña:—

“Dentro de un pobre pesebre

y cobijado con heno

yace Jesus Nazareno.

En el heno yace echado

el hijo de Dios eterno,

para librar del infierno

al hombre que hubo criado,

y por matar el pecado

el heno tiene por bueno

nuestro Jesus Nazareno.

Está entre dos animales

que le calientan del frio,

quien remedia nuestros males

con su grande poderío:

es su reino y señorío

el mundo y el cielo sereno,

y agora duerme en el heno.

Tiene por bueno sufrir

el frio y tanta fortuna,

sin tener ropa ninguna

con que se abrigar ni cubrir,

y por darnos el vivir

padeció frio en el heno,

nuestro Jesus Nazareno.”

More of a peasant flavour is found in some snatches of Christmas carols given by Fernan Caballero in her sketch, “La Noche de Navidad.”

“Ha nacido en un portal,

Llenito de telarañas,

Entre la mula y el buey

El Redentor de las almas.

* * * * *

En el portal de Belen

Hay estrella, sol y luna:

La Virgen y San José

Y el niño que está en la cuna.

En Belen tocan á fuego,

Del portal sale la llama,

Es una estrella del cielo,

Que ha caido entre la paja.

Yo soy un pobre gitano

Que vengo de Egipto aquí,

Y al niño de Dios le traigo

Un gallo quiquiriquí

Yo soy un pobre gallego

Que vengo de la Galicia,

Y al niño de Dios le traigo

Lienzo para una camisa.

Al niño recien nacido

Todos le traen un don;

Yo soy chico y nada tengo;

Le traigo mi corazon.”

In nearly every western language one finds traditional Christmas carols. Europe is everywhere alive with them; they spring up like wild flowers. Some interesting Italian specimens are given by Signor de Gubernatis in his “Usi Natalizi.” Here are a few stanzas from a Bergamesque cradle-song of the Blessed Virgin:—

“Dormi, dormi, o bel bambin,

Re divin.

Dormi, dormi, o fantolin.

Fa la nanna, o caro figlio,

Re del Ciel,

Tanto bel, grazioso giglio.

Chiüdi i lümi, o mio tesor,

Dolce amor,

Di quest’ alma, almo Signor;

Fa la nanna, o regio infante,

Sopra il fien,

Caro ben, celeste amante.

Perchè piangi, o bambinell,

Forse il giel

Ti dà noia, o l'asinell?

Fa la nanna, o paradiso

Del mio cor,

Redentor, ti bacio il viso.”

With this lullaby may be compared a singularly lovely and quite untranslatable Latin cradle-song of unknown origin:—

“Dormi, fili, dormi! mater

Cantat unigenito:

Dormi, puer, dormi! pater,

Nato clamat parvulo:

Millies tibi laudes canimus

Mille, mille, millies.

Lectum stravi tibi soli,

Dormi, nate bellule!

Stravi lectum foeno molli:

Dormi, mi animule.

Millies tibi laudes canimus

Mille, mille, millies.

Ne quid desit, sternam rosis,

Sternam foenum violis,

Pavimentum hyacinthis

Et praesepe liliis.

Millies tibi laudes canimus

Mille, mille, millies.

Si vis musicam, pastores

Convocabo protinus;

Illis nulli sunt priores;

Nemo canit castius.

Millies tibi laudes canimus

Mille, mille, millies.”

Curious little poems are found in Latin and other languages, making a dialogue of the cries of animals at the news of Christ's birth. The following French example is fairly typical:—

“Comme les bestes autrefois

Parloient mieux latin que françois,

Le coq, de loin voyant le fait,

S’écria: Christus natus est.

Le bœuf, d'un air tout ébaubi,

Demande: Ubi? Ubi? Ubi?

La chèvre, se tordant le groin,

Répond que c'est à Béthléem.

Maistre Baudet, curiosus

De l'aller voir, dit: Eamus;

Et, droit sur ses pattes, le veau

Beugle deux fois: Volo, Volo! ”

In Wales, in the early nineteenth century, carol-singing was more popular, perhaps, than in England; the carols were sung to the harp, in church at the Plygain or early morning service on Christmas Day, in the homes of the people, and at the doors of the houses by visitors. In Ireland, too, the custom of carol-singing then prevailed. Dr. Douglas Hyde, in his “Religious Songs of Connacht,” gives and translates an interesting Christmas hymn in Irish, from which two verses may be quoted. They set forth the great paradox of the Incarnation:—

“Little babe who art so great,

Child so young who art so old,

In the manger small his room,

Whom not heaven itself could hold.

Father—not more old than thou?

Mother—younger, can it be?

Older, younger is the Son,

Younger, older, she than he.”

Even in dour Scotland, with its hatred of religious festivals, some kind of carolling survived here and there among Highland folk, and a remarkable and very “Celtic” Christmas song has been translated from the Gaelic by Mr. J. A. Campbell. It begins:—

“Sing hey the Gift, sing ho the Gift,

Sing hey the Gift of the Living,

Son of the Dawn, Son of the Star,

Son of the Planet, Son of the Far [twice],

Sing hey the Gift, sing ho the Gift.”

THE FLIGHT INTO EGYPT: THE REST BY THE WAY

MASTER OF THE SEVEN SORROWS OF MARY

(ALSO ATTRIBUTED TO JOACHIM PATINIR)(Vienna: Imperial Gallery)

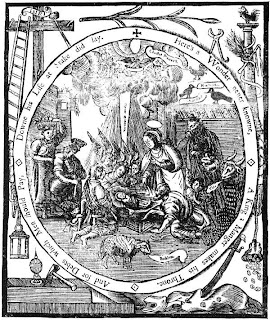

SINGING “VOM HIMMEL HOCH” FROM A CHURCH TOWER AT CHRISTMAS.

By Ludwig Richter